Even in his very first film, The President (1920), Dreyer made a point of using the film set to convey part of the portrayal of personality. He wrote in a letter1,that the surroundings should reflect the personality of the characters, "while at the same time I also strived for simplicity", and revealed that painters such as Whistler and Hammershøy had been an inspiration in his work.2 With his second film, Leaves from Satan's Book (1920), he actually aimed to "produce a cinematic work which will be considered a classic work", and in a discussion about the film budget he made it clear to technical director Wilhelm Stæhr of Nordisk Film that the company might as well forget all about savings, because he had no intention of making a "standard film",and that only he could decide what was necessary and what was not, "as I already have every shot, just as I intend it, present in my consciousness". There was "nothing (...) superfluous, unnecessary or random" in his screenplays. "The pictures form an organic whole."3

Visual opera

In his fourth film, Love One Another (1921), he masters both crowd scenes and scenes of persecution during pogroms in a Russian town, as well as more intimate scenes. This wide range in the association of characters and their surroundings results, even in this early film, in a striking materiality and sensuality in the portrayal of milieux and visual impressions, such that the degree of saturation achieved by his film images leads to stylisation in the form of simplified structures and compositions.

This painstaking exploration of details in visual style as narrative practice is something that Dreyer worked to develop throughout his career; as an example, we might mention the opening scene of his final film, Gertrud (1964). The film's introductory scene lasts more than fifteen minutes, but contains just fourteen shots, while the core of the description of the stormy relationship between Gertrud and her husband Gustav can be reduced to just three shots. With few lines of dialogue, stylised camerawork and tightly-controlled character movements, the result is a piece of pure choreography for both camera and actors. At the end of the scene, Gustav walks over to the window and declares: "The evenings are growing darker." This is naturally pathos, but it is also an example of pure and highly extreme stylisation. The entire repertoire of camerawork, gestures, facial expressions, dialogue, lighting, picture composition and editing has been selected, purified and stylised down to the bone. As artistic style in the medium of film, this is visual opera.4

"Everything must be prepared"

In the same year that Gertrud was completed and received its premiere (18 December 1964 in Paris and 1 January 1965 in Copenhagen), Dreyer spoke about his thoroughness in film production and the uncompromising attitude to staging and visual style that he had first revealed in his debut as a film-maker for Nordisk Film in Valby in 1919. During a birthday interview for the Danish newspaper Ekstra Bladet (1 February 1964), in reply to a question on the importance of diligence and preliminary work, he said: "Everything must be prepared – if not, you might suddenly find yourself lacking an elephant." (A remark that I naturally made the motto for my book "Dreyers Filmkunst" in 1989.)

Dreyer's work with visual patterns

Dreyer is thus a director who works very consciously with visual patterns, right down to the stylistic micro-level. As a result, his films are a treasure house to explore for those who wish to learn about how meaning can be articulated through the materials of the film medium. The filmic elements are clearly combined to cause them to interact in particular patterns, with the aim of creating quite specific frameworks for the experiential possibilities of the audience. How, then, is the fictional universe structured in selected films from Dreyer's catalogue? The examples that follow in this article illustrate some of the aesthetic strategies that Dreyer applied in his visual style. What kind of cinematic space derives from his filmic and artistic choices, and what is the relation of this spatiality to perspectives, characters and narrative? How can we characterise the spatial realisation in relation to traditional cinematic spaces? A specific focus on his visual style may contribute to what has been called "the historiography of film style".5 By analysing stylistic features, it is possible to generalise and identify elements of Dreyer's cinematographic practice which represent specific filmic potentials, i.e. characteristics relating to the semantic and communicative dynamics and potential of the film medium as such.

Classic film vs. Dreyer's "combinatory dynamics"

What has become known as 'classic film' and 'classic film style' mainly developed within traditional American mainstream film. The visual style of these films has been described by David Bordwell and Kristin Thompsen as characterised by a 180° system, consisting in reality of a series of rules of thumb which are designed to secure a particular form of presentation and viewer experience of so-called natural spatial and chronological continuity.6 The implicit aim of the system is a 'naturalisation' of the cinematic space – it has been compared to realistic or mimetic painting, with its linear perspectives and naturalistic presentation.

But when Dreyer experiments with his personal articulation of the cinematic space, he is clearly not interested in presenting the audience with 'realistic' scenes, which possess continuity in space and time. Instead, he focuses on making use of what are actually abstract cinematic elements, and on finding various ways to combine these in a kind of "combinatory dynamics".7 Realistic' qualities in the visual presentation are not the central aspect of his films, which is rather the result of combinatorics that form a structure, presented on the screen as ideas, relations between the characters, or even attempts to interpret all of these. The film presents the total picture to the audience as an object of experience, reflection and discussion.

The omnipresent camera

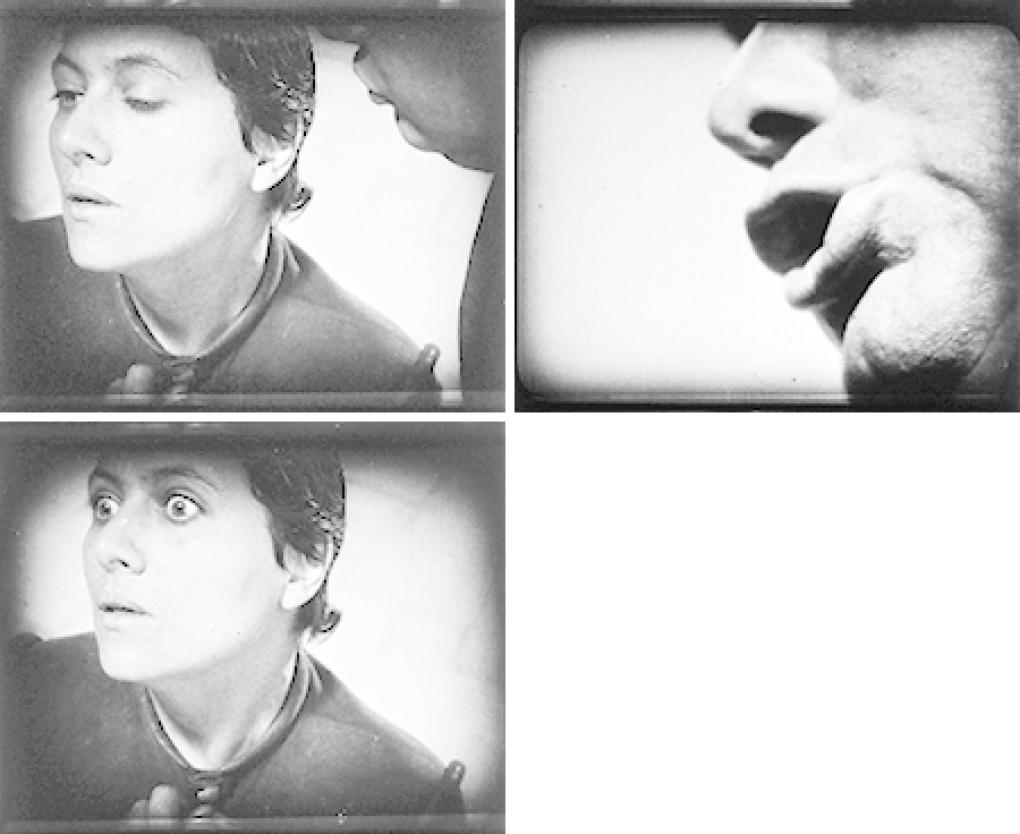

As an example of how the abstract elements in the visual style function, we might examine the beginning of The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), namely Joan's oath-giving and initial interrogation in the chapel, in which the camera shows her from various angles: from above and below, from the front, the rear, and diagonally from one side and another. This is a style of presentation reminiscent of the overlapping angles of "simultaneous spatial portrayal" in modern art, such as that of Picasso and the other cubists, in which the artist shows several sides of objects, bodies and faces at once. Dreyer combines this spatially free form of combinatorics with a 'flat' presentation similar to that of 'primitive medieval' art, in which, for example, two sides of a house might be represented on the two-dimensional surface of a painting without any attempt to reproduce spatial perspective in a modern sense.8 In Dreyer's work, the camera moves freely in all dimensions of space – around people, back and forth between them, and everywhere in the scenery, and in this way, that which is recorded from all these angles and positions is located in relation to the picture surface. This leads to a remarkable complexity of space and picture: an experience of multi-dimensionality in the encounter with the screen surface.

Directions in Dreyer's cinematic spaces are always logically and geographically correct, but their structure is consciously formed with a view to presenting them on the screen. It is a visual style that explores a range of the film medium's fundamental elements, and in the case of this scene emphasises, amongst other things, the psychological struggle that is taking place, and how Joan is under attack from all sides.

When, below, I suggest other ways in which it is possible to make use of, not just one point of view (i.e. a central perspective), but a whole series of camera positions and viewpoints in films, it is to emphasise that these are not only brought into play to produce a so-called credible and 'realistic' space. If we examine this idea more closely, it would appear that Dreyer's aim is rather to directly articulate the narrative in the visualisation of the films' universe and events.

The free camera in Thou Shalt Honour Thy Wife

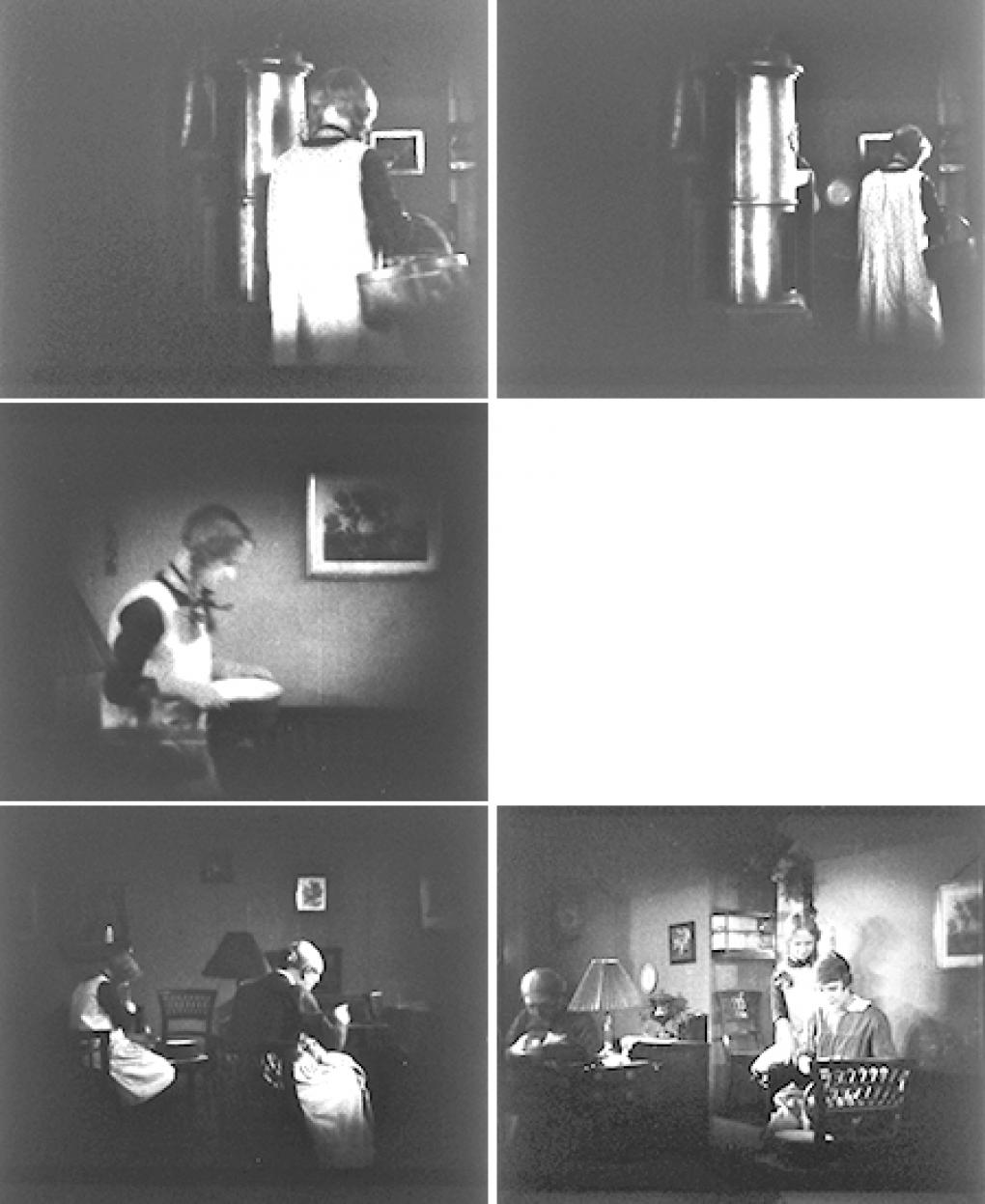

Thou Shalt Honour Thy Wife (1925) contains many examples of how Dreyer's camerawork and editing move freely, in a very simple, but clear and elegant manner, within the cinematic space. In one late afternoon scene, for example, while preparations are being made for the homecoming of Victor, the father, and the family's evening meal, there is a brief scene in which Dreyer experiments with the relationship between the possibilities of the camerawork and the presentation of space, and takes this further than in his previous films.

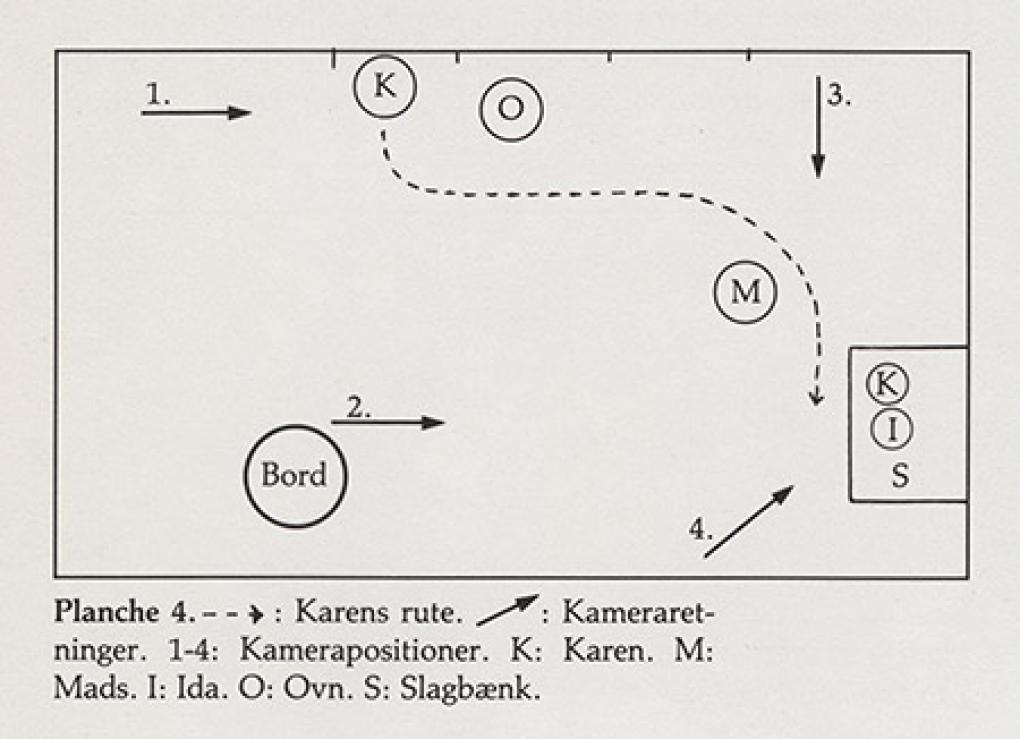

Mads (the housekeeper and Victor's former nanny) is sitting and sewing, mother Ida puts more fuel in the stove, and daughter Karen enters from the kitchen with a pot and a basket of potatoes, and sits down on the bench to peel them. But Ida takes over the work, because Karen must take care of her hands.

Together with cuts to the son, Frederick, on the house staircase, and the backyard, Dreyer presents this little sequence in a dense and subtle montage of directions, distances and individual movements (see pictures 3-7). From a corner behind the door, we see Karen enter the room, walk into the depth of the picture, and turn to the right (fig. A, position 1, pictures 3 and 4). A cut to a medium shot shows her sit down on the bench; the orientation of the camera towards the wall with the bench is the same, but the camera has been moved to the right and forward (position 2, picture 5). In the following medium long shot of Karen and Mads, the camera direction has been altered by 90° (position 3, picture 6), and with Ida's taking over of the potato peeling follows yet another shift to an oblique angle towards the bench (position 4, picture 7).

The spatiality of vision and the art of light

In the stylised presentation of several scenes, Dreyer uses elegant camerawork and editing to portray the mutual feelings of the characters and their consideration for each other, and he forces the audience so close to the atmosphere of the home that you can almost smell and hear it. In some passages the shots, with their details of actions and reactions, are quite unrealistically numerous, so that, rather than succeeding each other, they present different aspects of the same instant. The result is that fractions of seconds are lengthened into a kind of psychological slow motion. The effortless, almost underplayed portrayal of everyday life and its internal drama is the result of an interweave of directions and movements in a complex presentation of space. Dreyer thereby refines the experiences and ideas gained from Michael(1924) and earlier films by allowing the camera to move around in a completely free manner. One could almost speak of the dissolution of statically-defined two or three-dimensional space, with its height and breadth in the screen image and unambiguous depth effects, in favour of a multidimensional space.

Dreyer is thus developing his visual language in a direction which breaks down the idea of the camera as a fixed point; and this occurs, paradoxically enough, in the depiction of an apparently quite realistic and normal day. Dreyer is in the process of formulating or exploring the abstract narrative potential of film language and its formal minimum elements through a highly refined technique of constructing moving images into narration, rather than settling for a photographic recording. The core of the film's visual language, its style, is the special organisation of its directional changes, spatial differentiation and picture rhythms in the editing. At its heart lies Dreyer's exploration of the SPATIALITY OF VISION, and even in these early films, we can already sense the coming experience of film as the ART OF LIGHT. Several of the film's scenes reveal the enthusiasm that shines out of Dreyer's experimentation with the possibilities of dissolving and constructing cinematic space with his camera.

The cinematic life of Joan of Arc

In The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), as previously mentioned, Dreyer refined his principles of abstract construction. The relationships and logic of what ultimately appears on the screen do not seek to establish credibility based on so-called realistic continuity; one might rather say that this film displays visual compositions and patterns of design that are characteristic of Dreyer's exploration of cinema as a meaning-producing device that functions on the basis of stylistic principles. The camera is not locked into a specific, given 'logic' in the space which lies in front of it prior to shooting, editing and reproduction. The final cinematic space which results is planned, recorded and completed with its film image in mind, including its surface dimensions and its characteristics of a longitudinal mosaic, together with the sequential presentation of this mosaic. In principle, a film, with all its individual shots, is simply one long picture, which merely alters all the time, in time.

In the interrogation scene in the chapel, as well, the camera practically jumps around Joan. The visual style or 'camera architecture' is an expression of the freedom of the camera, and it assigns a higher priority to the image space than to the space of the scene. There is no privileged perspective, apart from considerations of the relationship between the individual shots in the completed sequence. The architecture of the film's space consists of light, air and directions of gaze, and is created by camera locations and angles which become the entry point of the audience into the narrative that Dreyer portrays on the screen.

Dreyer's mania for composition

What is characteristic about The Passion of Joan of Arc is the actual manner in which Dreyer combines the individual elements to create the whole. Part of the film's experiment par excellence consists of the way in which the whole is built up from the details – and the consequent omission of unnecessary communication and transitions. The totality of the experience is mainly achieved through the free, mobile camera, which is not a camera that continually tracks, pans, shakes or tilts (although these movements are naturally present) but rather one that is weightless, privileged to take up any position and present its image from the chosen viewpoint – and in the next moment, to reveal an entirely different side of this (e.g. the images of Joan during the swearing of the oath). Dreyer positions the camera freely – and thereby builds up meaning and experience on the basis of his choices of visual elements of style. The freedom of movement in three-dimensional space is different from that of more conventional films, which, as mentioned, go to a great deal of trouble to create the illusion of realism and three-dimensionality. Dreyer, on the other hand, insists on the two-dimensional and visual character of the individual shot – hence his composition mania and work with the potential of all possible angles in the cinematic space. For him, space is not 'one-eyed', but full of potential views, possible 'gazes'. This space, rather than being concentric, is 'ex-centric'. One could almost speak of centrifugal space and camerawork.

In considering The Passion of Joan of Arc, we should probably keep the time of its production in mind. This was the mid-1920s, when this kind of cinematic composition was innovative and pioneering work, otherwise only seen in the production of the greats of film history, such as Eisenstein, Murnau and Stroheim. Dreyer works on many levels with patterns of elements in the meaning-creating process of film language: bodies, hands, faces, eyes, objects, spaces, spatial areas, etc., as well as with different angles, perspectives, distances, framings, compositions and rhythms: elements which do not in themselves make sense as narrative, but which become narrative in the overall combinatorics.

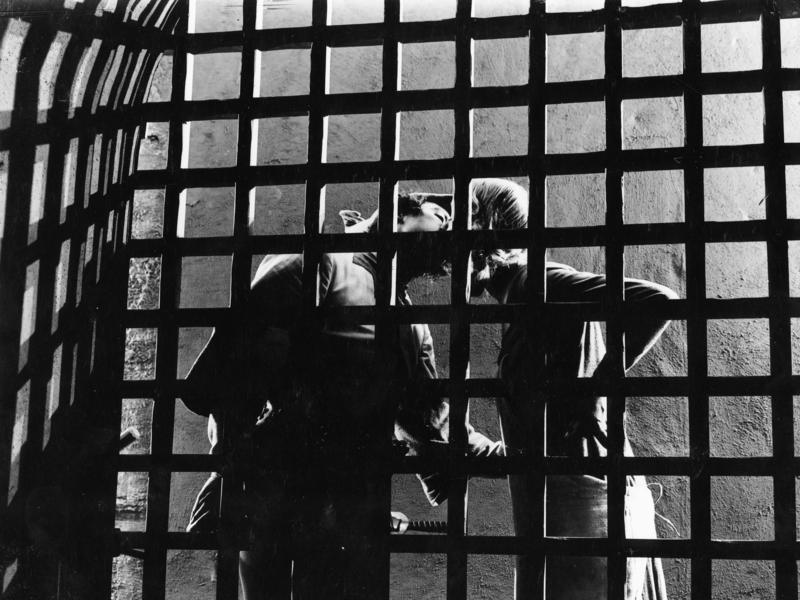

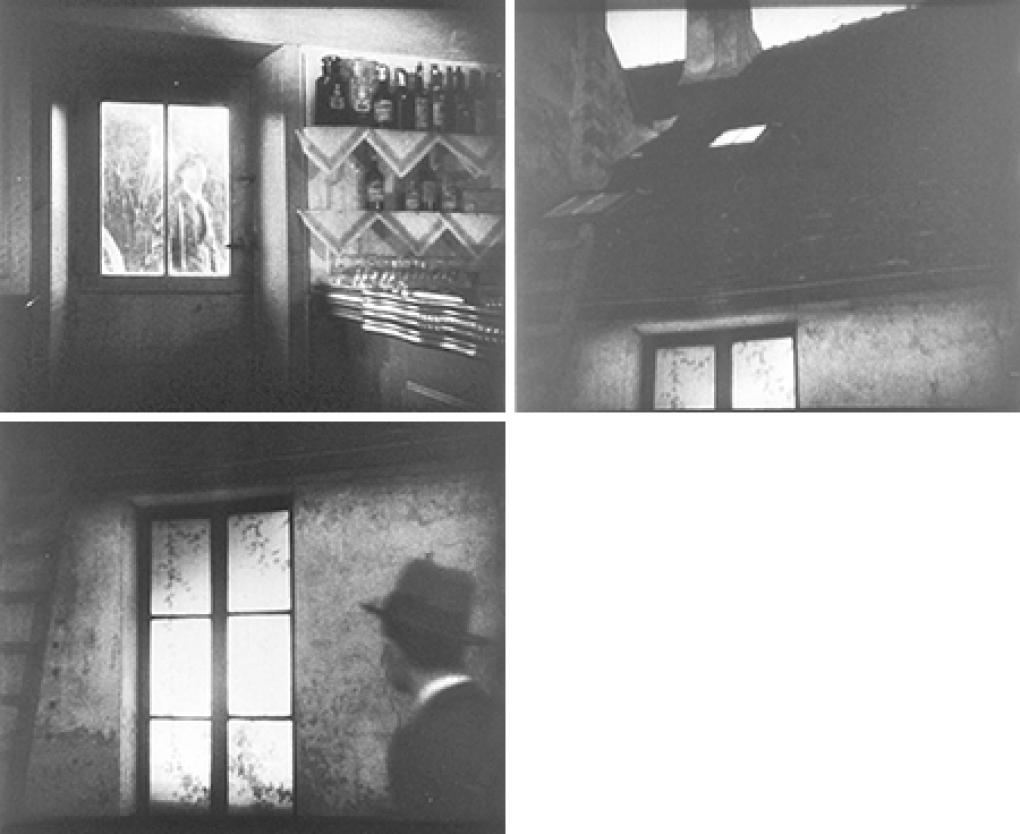

The labyrinth of images in Vampire

When the main character in Vampire (1932) arrives at an inn at the beginning of the film, Dreyer at several points deliberately switches between what the character can see, and what he cannot see. But not only that: one of the characteristic features of the film is precisely a play on the viewer's doubts about what it is you are actually seeing, and from which perspective. This is an important element in building up the sense of mystery in Vampire. An illustration of this playing with perspectives and the audience's attention is revealed in the scene in which Gray waits outside the inn, and in his contact with the girl who opens the door for him. Gray is first of all seen through a pane in the door. Receiving no response, he steps back and looks up. There is a cut to a low-angle view towards the roof, followed by a pan to the left. From a dormer window and a chimney, the camera movement tilts directly down over the roof and towards a window with light in it. The montage of the two shots with Gray and the roof naturally leads the viewer to associate the view of the roof, etc., with Gray's point of view; the camera movement seemingly reproduces Gray's searching gaze. But he then walks in from frame right and over to the window!

Trickery with points of view

When Gray enters the picture, it shows that the panning and tilting did notrepresent the character's subjective point of view; his entry reveals that Dreyer has 'tricked' us. But if we examine this more closely, it becomes clear that this 'trickery' is revealed, not just by Gray's entry into the shot, but already in the cut from the inn door to the roof. Gray looks upwards to the left in relation to the door, but the camera angle begins diagonally upwards to the right and does not point left until after the pan. His entry into the picture confirms that the building, right from the start of the shot, has been seen from a perspective other than Gray's.

Several other examples demonstrate this objective position of the camera in relation to the protagonist, and although Dreyer naturally also shows what Gray sees, the point is that identification via the subjective camera is made impossible through Dreyer's artistic and stylistic choices. The possibility is toyed with, but in the actual use of the camera, the film radically differentiates itself from the point of view of the person concerned. Dreyer wishes to show the characters' situation from the inside and with understanding, as in other films, but insists at the same time in the narrative style that, as examples to emulate, or not, we must be able to see the characters from outside, without the sentimentality and reflection-smothering choice of identity with which the products of the Hollywood-dominated film industry were already then influencing the audience's habits of sensing and understanding.

Dialogue-provoking cinematic art

This stylistic subtlety demonstrates a subjectivity ambiguity – which results in dizzying consequences when Gray not only dreams about himself, but dreams, that he dreams, that he sees himself dead. In several layers, we are presented with a play reminiscent of those dreams in which you not only participate as a player, but are also literally beside yourself as an observer. This aspect of Vampire is a play with built-in disavowals of the subject's status as the centre of the narrative, as well as of the idea of the camera as a centre and an extended arm of an authoritative narrator who possesses the only correct view, which must be imparted to the audience in his and only his version. Here we can see the preliminary result of trends, which were already present in Dreyer's earlier camera use and narrative style, developed to the highest degree in the dissolution of space in Thou Shalt Honour Thy Wife and The Passion of Joan of Arc through the presentation of multidimensional psychological space by the omnipresent, liberated camera. It is a choice of style that also represents a narrative attitude to the chosen material – and which, after the experience acquired via the black holes of horror in Vampire, also gains a decisive influence on the interpretations that Dreyer presents to the audience for debate in the three major works Day of Wrath (1943), The Word (1954) and Gertrud 9. As is typical of Dreyer's efforts throughout his production, the visual style contributes to maintaining a balance between empathy and discussion, provoking questions and reflection rather than providing answers and ready-made conclusions. The visual style turns his work into a centrifugal and dialogue-provoking piece of cinematic art.

These non-centred and non-stable film universes, in which exploration and experimentation are key, testify to a modern experience that Dreyer has in common with more recent directors such as Antonioni, Bunuel, Godard, Fellini, Kubrick, Scorsese, Jarmusch and Lynch. No individual character and no fixed camera perspective can provide a secure centre.

The importance of the close-ups is a myth

With its mobility, Dreyer gains an untamed camera. It is a camera that is obsessed with seeing: the very fact of seeing relationships between people, their situation and conditions. Dreyer is obsessed with seeing this and showing it. In his work we encounter a highly-charged camera, and if we follow it in its detail and finer points, it places us on tenterhooks. The oft-claimed significance of Dreyer's interest in eyes and faces is however something of a myth – albeit one to which Dreyer himself gave nourishment in a number of statements. It is easy to exaggerate the importance of close-ups in the psychological portrayals in his films. I do not thereby wish to deny that they are an important feature, but simply to emphasise that they function only as a single element in the whole to which they belong, which is the most important aspect. Close-ups do not say very much in themselves, and Dreyer's facial close-ups do not always communicate as much as has been traditionally maintained. Moreover, close-ups, just like all other shots in a film, only attain their final meaning in context, with the result depending not just on the shot itself, but on its precise juxtaposition to other shots. It is in the interplay between shots in the composition of the sequences, i.e. in the montage, that "it" arises.

Pure film

One of the many things I have tried to explore by analysing the style and themes of Dreyer's films is whether and in what way one could say that he endeavoured to practice the making of pure film – not as a kind of ultimate goal, but as a means of developing new and engaging solutions to cinematic and narrative issues. His stylistic technique and refinements, ambiguities and leaps in time and space became united in a new media and camera-conscious creation of cinematic worlds in the true sense of the term. He creates fictional universes which are more genuinely cinematic than the illusive construction of so-called spatial continuity in conventional films. This may well involve breaches of the conventions governing what should be presented to the audience, but the key factor is the construction, or invention, of the camera-mediated space.

With his camerawork and editing, Dreyer builds up an entire network around his characters, and makes this field the basis of his narrative practice. His style, as a form of expression, constitutes quite simply the foundation of his cinematic statements. When there is no longer an "I" to tell the story, no conventional figure with whom to identify or who can function as the mouthpiece of the director, then only picture-making, the actual visual narrative pattern, remains – i.e. only the semantic constructions produced by his gesticulating camera. This image network comprises both what is told, and the basis upon which it is told. The film is a gesture that has meaning. Like an architectural arch, it becomes a self-supporting semantic structure. Dreyer does not, in other words, tell the story from a single angle; instead of a marked, omniscient narrator who stands above the world of the characters, in Dreyer's films the narrative seeks a pathway between them. The visual style establishes patterns and carefully-crafted spaces which, in total, contribute to semantic universes for the viewer to identify and pursue.

Notes

1. Letter to Erik Ulrichsen on 11 March 1958: cf. Kau: "Dreyers Filmkunst", pp. 17-18.

2. Cf. the comparison between painting and film in Kau: "Dreyers Filmkunst, pp. 20-21.

3. Letter reproduced in Kau, "Dreyers Filmkunst", pp. 392-93.

4. This film also includes other clear examples of Dreyer's sources of art historical inspiration, cf. the references to Hammershøy in Kau, "Dreyers Filmkunst", pp. 358 and 373.

5. David Bordwell: "On the History of Film Style", p. 6.

6. Bordwell & Thompson: "Film Art. An Introduction", pp. 310-17.

7. Cf. Kau: Dreyers Filmkunst, pp. 381-84.

8. Several film analysts and theorists have referred to these characteristics of painting. Vance Kepley writes: "In some respects the classical style resembles the perspective system of Western painting. Both are highly conventional sets of techniques which are widely perceived to be natural modes of representation. The perspective system presumes to portray a real-world scene from the fixed perspective of an ideal observer, while the classical cinema seems to define a real space viewed from several vantage points." (in "Spatial articulation in the classical cinema").

Similarly, Bordwell and Thompson refer to modern art, cubism and other forms of abstract painting when discussing modernist films: "French painters depicted several sides of objects, as if they were seen in an impossible space from several viewpoints at once. This movement became known as Cubism." ("Film History. An Introduction", p. 82.).

9. In Vampire, the existential reflections and reflections on the media and art (including the issue of suicide) attain a veritable meta-level. The built-in reflection on the medium's possibly life-consuming potential for building up fictional worlds, and the associated artistic issues, give Vampire a position in Dreyer's production which could be compared with that of Lost Highway in the work of David Lynch, as a central milestone in terms of cinematic language and artistic development. With this film, he, too, saw both tantalizing and alarming prospects in the potential of cinematic art.

Literature

Bordwell, David (1997). On the History and Film Style. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bordwell, David & Thompson, Kristin (2003) [1994]. Film History. An Introduction. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Bordwell, David & Thompson, Kristin (2004). Film Art: An Introduction (7th ed.) N.Y.: McGraw-Hill.

Kau, Edvin (1989). Dreyers Filmkunst. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

Kepley, Vance (1983). Spatial articulation in the classical cinema, in Wide Angle, vol. 5, no. 3.

By Edvin Kau | Translation by Billy O'Shea.

Watch the films on Danish Silent film: