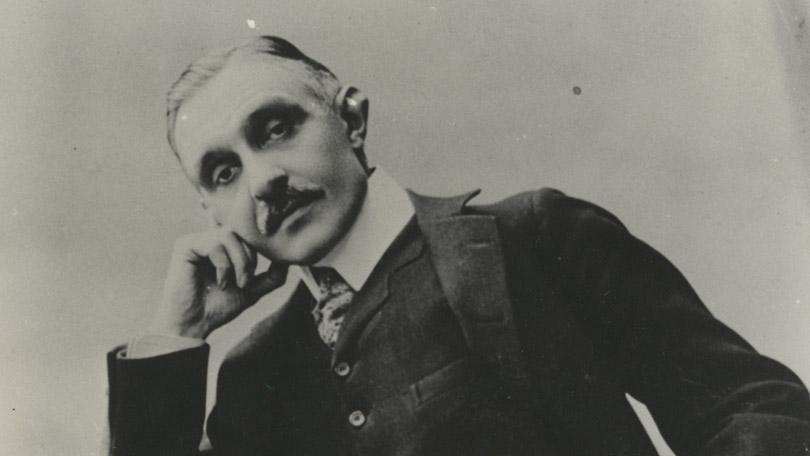

Though it was not Dreyer’s personal choice to adapt Herman Bang’s (1857-1912) novel Mikaël, he was fully satisfied with his German-produced film Michael. "My darling child" and "my baby more than the others," he even calls this, his sixth film, in two 1926 interviews (cf. Casper Tybjerg: Sandhedens Masker, Kosmorama No. 234, p. 60). Erich Pommer, the producer at the UFA studios in Berlin, in early 1924 suggested adapting Bang’s novel – and Dreyer barely hesitated to sign on to the project. Dreyer had already been thinking about adapting Bang’s novel Tine (1889). Working as a special correspondent, Dreyer once made a European trip, accompanied by Einard Skov of the Politiken newspaper, and interviewed Bang in Berlin a few years before the Danish author’s death in 1912. Unfortunately, the interview is impossible to locate today. Perhaps it was never finished and published.

Why Mikaël?

If Dreyer could have had his choice, he would probably have chosen to adapt a different work by Bang. This is indirectly evident from an interview published in the journal Hver 8. Dag (6 Nov. 1924), in which Dreyer makes the following qualified praise of Mikaël, "I do not find 'Mikaël' to be Bang’s best novel.

There is so much tinsel in it, so much of the external. But it has a grand and beautiful line. It contains pure tragedy, it is carried by true melancholy and is filled with a compressed atmosphere." Nonetheless, now that Mikaël had been chosen, Dreyer considered it important to accommodate his source material as far as possible. An interview Dreyer gave to Erik Ulrichsen for Kosmorama No. 49 in 1959, marking the occasion that Michael had been found, makes it clear that Dreyer strove to follow Bang closely. In the Hver 8. Dag interview, Dreyer stresses that his criterion for casting the film was that every single actor possess the personality of the character as portrayed in the novel. Moreover, Dreyer thought it highly important to depict the homosexual conflict as discreetly as Bang had done.

Bang, a popular writer in Germany

Pommer, the producer, chose Bang not only because Bang was a fellow countryman of Dreyer, but also because Bang in the 1920s was still an internationally recognised and popular writer, not least in Germany. The German programme for the film illustrates Bang’s popularity: it is taken up entirely by an enthusiastic tribute essay to Bang written by Willy Haas, one of the most respected German film critics of the 1920s. Dreyer and the film itself are barely mentioned. In his conclusion, Haas even elevates Mikaël to the status of international literary classic, a position the work has been hard pressed to maintain.

Man, a creature of passions

In literary history, Herman Bang falls under Impressionism, a French-inspired, more aesthetic approach to Naturalism that focuses on purifying a scientific, objective narrative technique more than on socially critical content. Bang’s books are distinguished by a pessimistic determinism, in which the fact that human beings are controlled by heredity, the environment and sexual drives precludes any faith in a higher meaning to life. "After all, we are all here for reproduction," a famous line from Ved Vejen ["By the Roadside"](1886) goes. In all of Bang’s writing we find this resigned attitude to man as a creature of passions. Even so, Bang never became part of the Brandesian wave in Danish literature, not only because it was hard for the Brandes brothers, Georg and Edvard, to accept his homosexuality, but also because he was unable to regard a positivistic view of life as fully liberating.

Mysticism and superstition

In Bang’s later writing, the naturalistic aspect is toned down a bit and the Darwinist-pessimistic worldview is joined by a flirtation with some of the purplest elements of mysticism, including spiritualism and palmistry. The latter phenomenon appears in Mikaël, in the extended opening scene at Zoret’s dinner party, when Mrs. Adelsskjold reads Mikaël’s palm and concludes that he is in reality "brutal." Bang evidently supports that conclusion, which serves as a prophecy, because Mikaël in the end does emotionally treat Zoret rather brutally. In this connection, it is interesting to draw in Dreyer’s manuscript, since it contains many scenes from the novel that did not make it into the final film. The manuscript reveals that Dreyer had originally intended to include the mystical scene.

Inner turmoil, outbursts of emotion

Bang writes some of his purest Impressionistic works in the last half of the 1880s, a phase he more or less concluded with Ludvigsbakke [a place name] (1896). These are the works that scholars call almost filmic. Mikaël, however, was written at a time when Bang had largely replaced detached Impressionism with a narrative technique widely employing internal views of the characters and a more prominent omniscient narrator. Moreover, inner turmoil and external outbursts of emotion are now more directly and openly described with verbal pathos. This change, heralded in two slim volumes of memoirs, Det hvide Hus ["The White House"] (1898) and Det graa Hus ["The Grey House"] (1901), also points back to Haabløse Slægter [Families without Hope] (1881), Bang’s scandal-embroiled first novel.

Misfit

The novels and short stories in which Bang employs this more omniscient and outright emotionally engaged narrative technique are thematically related. They are all works in which he treats central themes of his own private life, specifically his relationship to his mother and his homosexuality. Most literary critics and Bang scholars agree that Mikaël has become too didactic about the issues it treats, because the theme of an older artist’s unhappy, partially unrequited homosexual love of a young bisexual student is too close to Bang himself (and his unrequited love for a young actor, Fritz Boesen). He simply could not gain the necessary distance to his material. However, a recent contribution to the body of Bang scholarship, Dag Heede’s Mærkværdige Læsninger [Peculiar Readings] (2003), does not take this negative view of Mikaël. On the contrary, Heede claims that Bang succeeded in making the novel the most extreme example of a recurring thematic ambivalence and split in all his works of fiction, that is, the inner split between praising beautiful heterosexual love, on the one hand, and feeling like an outsider and a misfit, on the other. The character of the outsider appears in Bang’s works either as a man with homosexual tendencies or a spinster leading a "quite existence."

By Morten Egholm | 22. May